Listen to the latest episodes of Revolution Square Podcast. We sat down with Prof A.D Pandey to talk about Education, Academia, and Research. RS Podcast episodes are available to stream on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, and YouTube

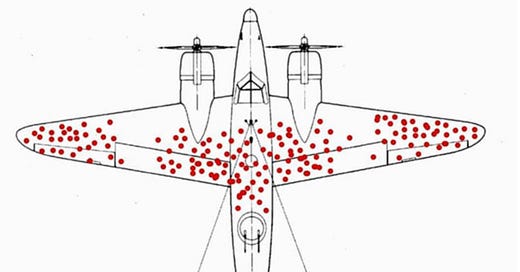

During World War II, the US military wanted to minimize the loss of bomber aircraft to enemy fire. The researchers studied the damage incurred by the bomber aircraft that returned from the mission. They suggested the armour should go to the places where the aircraft sustained most damage (bullet holes per square foot) like wings, fuselage, and other parts of the aircraft.

To understand the optimum use of armour, the military approached Abraham Wald, a member of the Statistical Research Group (SRG) at Columbia University. Looking at the data, Wald pointed out the mistake of studying the aircraft that survived the enemy fire. Certainly, it was not the answer the military expected. Wald suggested the armour should not go where the bullet holes are, but where they aren’t; engines. It is alright for the bomber aircraft to take damage anywhere on the surface except on engines and return safely because those who took the hit on engines never returned to the base. In decision making, the error to overlook things that are hidden behind the veil of survivors is called Survivorship or Survival Bias.

Source: Internet

When survivorship bias clouds our judgment, we tend to believe, emulate, and emphasize the success stories oblivious to the graveyard full of failures.

We come across a smiling old man in his 70’s with his grandchildren playing in the front yard of his home. He smoked his entire life, but we say he’s healthy. What we see is a survivor or an exception. What we don’t see are the martyrs who smoked just like the healthy-looking grandpa, but aren’t alive to tell their story. Warren Buffett, the 89-year-old mega investor drank five cans of Coca-Cola every day for 50 years, but do we ask others who had an unpleasant story to share?

Why do we see the terrible news of plane crashes making headlines for weeks altogether prompting us to believe that air travel is unsafe? If you were to publish the uninteresting news of a plane landed safely, it wouldn’t survive against the news of the one that did not. The aviation safety statistic for 2019 is one fatal accident for almost two million flights.

It’s survivorship bias to conclude that you want to put your child in an expensive school because your friend’s so-called brilliant son/daughter went to the same school. What we fail to notice are those many parents who report their child’s poor performance who went to the same school.

We are full of biases. One of the steps while purchasing from the internet is to read the reviews of the product. While good reviews make a point, bad or critical reviews reveal more, especially when there is nothing but only bad or critical reviews. We tend to not purchase the product with nothing but only bad reviews. But that’s not always the case. Many who are reasonably happy with the product don’t take the pain to write a product review online than those who are unhappy with the purchase. That’s the reason bad or critical reviews tell you more about the utility/feature of the product you are willing to make a compromise on.

Similarly, on social media, we only publish the content we think is worth sharing, but what about those updates which didn’t survive our scrutiny. That’s where our life story is hidden. Historical monuments, retro songs, classical art/literature seem to be very good than the current counterparts because the cheap content from those times did not stand the test of time.

Who will tell us about a failed cricketer, failed actor, failed musician, failed dancer, failed politician, failed entrepreneur, or a failed business? It is grossly inappropriate for us to assume that stories from successful people define the course of our action/strategy. Success stories are outliers in the grand playing field, but they do not tell us the whole plot. We should look up to successful people for inspiration, but learn from those who failed in order to succeed.

How we avoid survivorship bias is by aggressively seeking the absolute truth. Correlation does not mean causation. Rather than confirming, it is worthwhile to pause, reflect, and question our biases when presented with a narrative. For example,

Why do I believe in it?

How is this conclusion true and why should it be so? Can I disprove it with factual data before I accept it?

Can I find any examples contrary to the story?

What’s the missing data?

If you haven’t realized it already, we are moving towards thinking from First Principles; to seek the truth.

RS Podcast on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, and YouTube

All posts from Revolution Square are free to view and will remain so in the future. If you love what you see and can afford, support Revolution Square by becoming a paying subscriber.